Half of residents around Druid Hill Park do not own cars. So why does the area feel like a suburban highway?

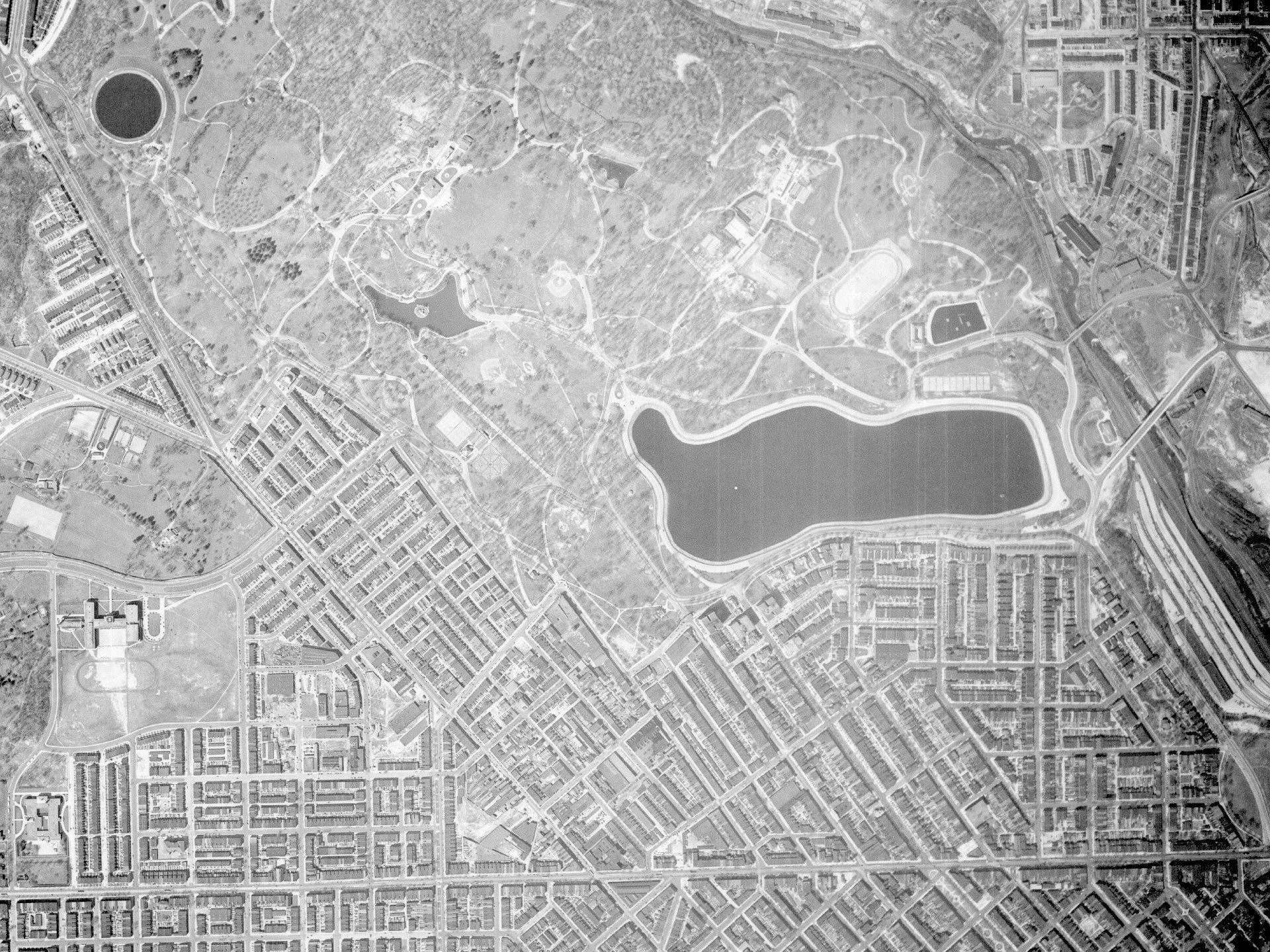

From the 1940s through the 1960s, car-focused transportation projects drastically changed the face of the park. The city’s goal was faster commute times for downtown workers living in the suburbs. Back then the surrounding neighborhoods of Reservoir Hill and Mondawmin were largely Jewish and African American communities. Proposed in 1945, the “Druid Hill Expressway” would convert Druid Hill Avenue and McCulloh Street to one-way thoroughfares connecting with a widened and extended Auchentoroly Terrace. By 1947 the highway plans had sparked a robust public debate.

In his Baltimore Sun op-ep on the history of the highways around the Druid Hill Park, local resident Dr. Daniel Hindman uncovers how the city ignored the voices of African Americans:

In shaping this plan, the city did not seek input from the primarily African American and Jewish communities through which the proposed expressway would travel. When the plan was put through The Commission on City Planning, the lone dissenting member was John L. Berry, a man The Baltimore Sun identified at the time as the “negro member of the commission.” Despite Mr. Berry’s opposition as a representative of the community that the proposed route and accompanying traffic would directly affect, the city moved forward. Civil rights advocates, including Lily Jackson and Clarence Mitchell, would later assist in resisting the project, but to no avail.

When the “Druid Hill Expressway” was proposed, NAACP Labor Secretary Clarence Mitchell Jr. argued that increased traffic speeds through westside neighborhoods would imperil black residents, individuals barred by racist real estate practices from moving to the very suburbs that the highway would serve. Shaarei Tfiloh synagogue Rabbi Nathan Drazin wanted to ensure that traffic would not endanger children attending Hebrew school as well as the throngs of congregants who traditionally walked down the middle of Auchentoroly Terrace during the high holy days.

Despite local outcry over the expressway plans, the three local council members were asked by area political boss James Pollack to ignore the opposition of their constituents and instead support the “city wide” highway effort. In those days, Pollack’s Trenton Democratic Club ran a political machine that picked and elected almost all northwest Baltimore politicians. While the councilmen had local independence, they dared not cross Pollack over issues he considered important to the city at large. Conveniently, the expressway plan called for widening and extending Auchentoroly Terrace to Anoka Avenue – the calm, tree-lined street that Mr. Pollack called home. In the end, the councilmen appeased the local political machine, and they voted in favor of cutting down over 250 trees in Druid Hill Park to make room for widening Auchentoroly terrace into a highway, eliminating the historic and safe access to Druid Hill Park that residents of West Baltimore had so long enjoyed

Just a few years later, on the south side of the park, residents of Reservoir Hill found themselves facing a similar fate. In 1951, Mayor Thomas D’Alesandro Jr. proposed the Jones Falls Expressway. Druid Park Lake Drive would need to be expanded to serve as a feeder road to this new highway. Ensuing years of residents’ protests were ignored and construction began in 1956.

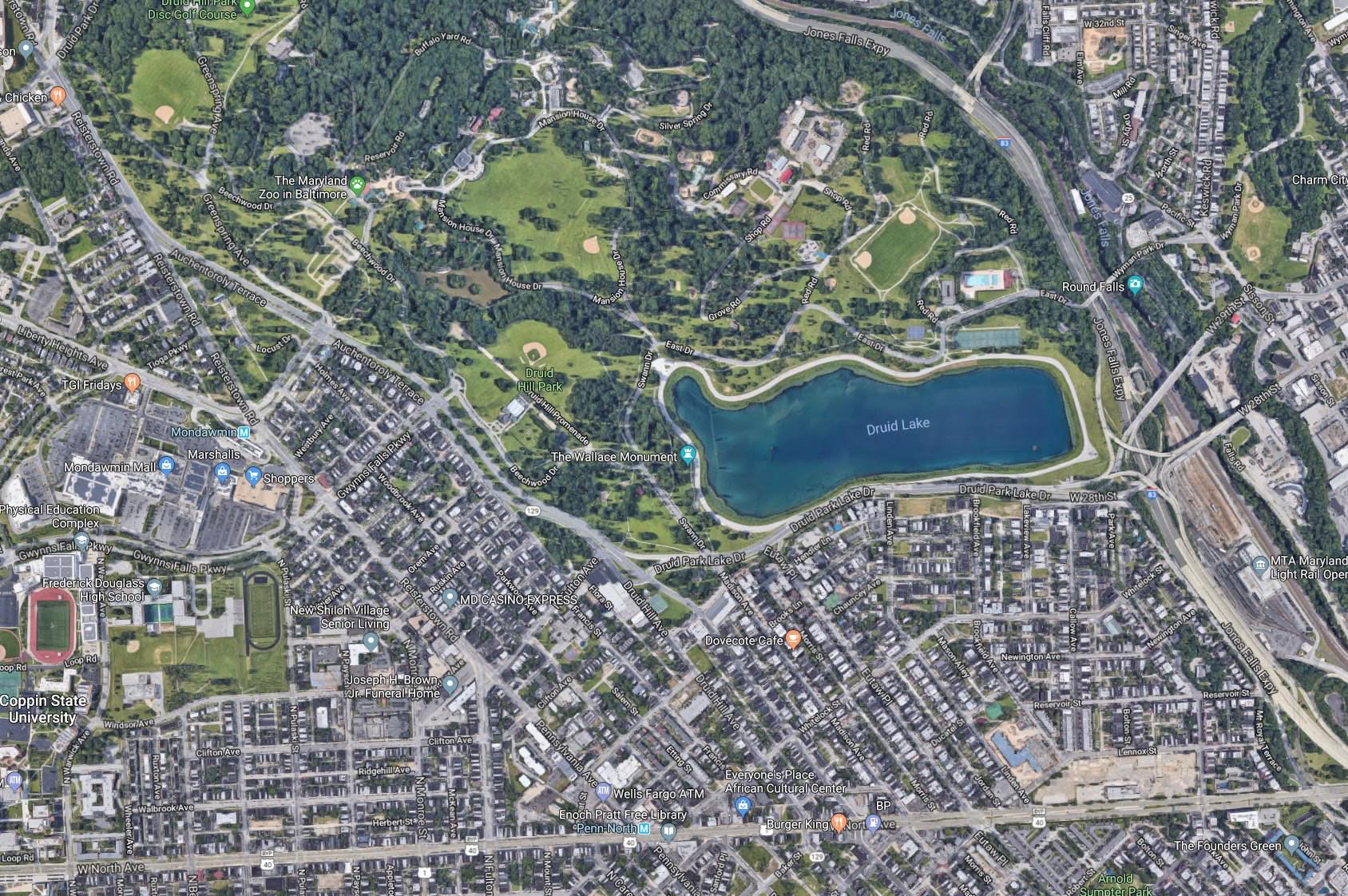

By 1963, with the completion of the Druid Hill Expressway and the Jones Falls Expressway, what were once two-lane, park-front residential streets now served as dangerous five-to-nine-lane highways. The roads have made it difficult for people to cross on foot into the park, and for disabled individuals who live in Lakeview Towers, a public housing high-rise immediately adjacent to the park, crossing by wheelchair is nearly impossible. A park once served by over 20 footpath entrances is now equipped with only five sets of deteriorating, nearly invisible crosswalks.

The planning decision to build highways around Druid Hill Park, a decision rooted in historic, structural racism, makes it difficult for the existing working class population – people of color living in Auchentoroly Terrace, Mondawmin, Penn North, and Reservoir Hill – to fully benefit from the park as a public health amenity. The Health Department’s 2017 Neighborhood Health Profiles shows that the majority lower income, African American communities around the park have some of the city’s highest mortality rates of cardiovascular disease and cancer. Census data also shows that nearly half of neighbors around the park do not have access to cars. As pedestrians, wheelchair riders, transit users, and people who rely on bicycles, neighbors deserve priority access to the park.

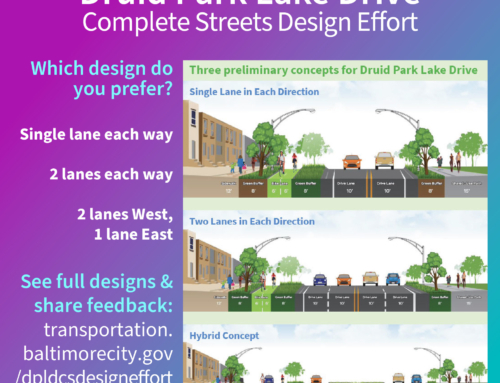

Seventy years after the first highway was built around Druid Hill Park, there is now a movement afoot to rethink how these barrier roadways can become connectors enabling more equitable access to Baltimore City’s historic, 714 acre green space. In 2017, Councilman Pinkett convened the Druid Hill Park Stakeholders group in an effort to counteract years of urban planning that has prioritized the movement of cars through the community over the wellbeing of the people who live in the community. We are advocating for “complete streets” to safely connect our neighborhoods with Druid Hill Park. Complete streets are streets designed and operated to be safe and accessible for all, including pedestrians, children, seniors, mobility users, transit riders, and bicyclists.

In February 2018 DOT agreed to conduct a major transportation study to address our communities’ concerns. In the second half of 2019, Baltimore City DOT will be conducting the Druid Park Lake Drive Design Effort. This study will address park access around the entire park, including Druid Park Lake Drive, Auchentoroly Terrace, Reisterstown Road, and Druid Park Drive. The schedule for this planning effort is still to-be-determined. During the study, residents will have the opportunity to shape a public vision for converting the dangerous highways around Druid Hill Park into complete streets streets safe and accessible for all. In order for the forthcoming plans be truly transformative and inclusive, we need as much resident input and active engagement as possible. Now is the time for us to TAP Druid Hill! Click here to get involved.